|

|

Post by Riothamus on Feb 16, 2005 9:49:32 GMT -5

I'm sorry, but that's bosh. Paul called Peter out--see Galatians 2:11-14. (Though I daresay, in your view, Paul could have lied,) There is no recorded instance in the Bible where Peter opposes Paul--as a matter of fact, in his epistles he speaks of Paul as an equal--equally inspired, equally endowed by the Spirit.

That's not at all what I'm saying. Faith in Christ, before and after His death, saved. No one can keep the Law--that is why Christ is necessary. It is through His Law-Keeping that we find peace with God. And it isn't God that put us under the curse of the Law--it was Adam. Before the fall he was able not to sin, but he chose sin, and so brought death into the world.

It's your worldview which is the unjust one. Because if "human beings only bear the consequence of [Adam's]sin, which is death," then God has indeed used His power unjustly, in the true sense of the word, for He punishes those who have no guilt as if they were guilty.

Apples and oranges. The fate of an infant is indeed a mystery; indications in Scripture are that there is some special grace for them. However, they have not, as yet, broken the Law. Whereas pagans commit actual sins--actual breakings of the law--and prostitute themselves to unclean idols and gods who are no gods, and this, together with the original guilt (which you deny, but which I maintain exists nontheless,) is utterly damning. To put it simply, the infant has not reached an age of accountability, while the pagan has.

|

|

|

|

Post by dinadan on Feb 16, 2005 10:39:17 GMT -5

It seems we have diametrically opposed views on this, and neither of us is going to give ground...so maybe we should call off the hounds and talk more about magic in literature--and hopefully someone else will wander into the forum. Not that I haven't enjoyed the debate, but (frankly) I see no futher point--except that our views on magick will be continue to be informed by our beliefs, but that's unavoidable anyway.

So, unsubtly changing the subject: What do you think about magic "systems" in various works of literature? We can start with Tolkien or Lewis, since we both seem familiar.

|

|

|

|

Post by Riothamus on Feb 17, 2005 9:58:25 GMT -5

We must not be so diametrically opposed, after all...I was considering the selfsame suggestion. ;D I've very much enjoyed crossing blades with you. Thank you for the challenging discussion.

Personally, I prefer Tolkien's system. It has the benefit of being thought out and actually systematic. Any magic worked is done so by nonhumans; and in fact, in some cases (such as Elven-work,) those who work the magic don't think of it as magical. It's part of their ingrained nature, which is something else entirely.

Lewis, especially in his children's books, was much less well-developed, though in general the rule holds. "Wizards" are in fact stars, et cetera. There's one exception, in Prince Caspian, but it isn't terribly serious. In the "Space Trilogy" it's another matter. The concept of "free spirits"--discussed earlier in this thread--is invoked. Now, as I've stated, in my opinion such beings present a problem theologically; however, in literature they're the ideal way to avoid tangling with "dark powers." However, even these spirits are discounted as a result of history "coming to a point," (something I do agree with--the development of potentialities,) and the power of Merlin becomes the power of the eildil (apologies to the shade of Mr. Lewis if I mispelled that....) that is, of angels. Now, if Merlin came to me today and told me that interstellar angels were empowering him, I would call either Bellvue or an exorsist; however, in the fictional world this way works as well as any other, and is very effective. My only gripe, therefore, is that here "magic" (though not true magic,) is transposed from its proper realm--faerie, if I may plagerise Tolkien--into the "real world." I personally prefer that it stay in faerie--it is a potent natural force there, but is utterly un-natural here. Does that make sense?

As I say, I prefer Tolkien's system. He manages to have his cake--that is, human heroes, as well as wizards--without raising the spectre of Leviticus.

|

|

|

|

Post by dinadan on Feb 17, 2005 10:22:15 GMT -5

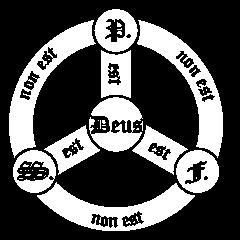

Interesting. What you call "faerie" I tend to think of as Broceliande (because of Charles Williams). One of themes in his poems is that Broceliande is, in some sense, the Otherworld, which touches our world and "The Land of the Trinity." It is through Broceliande that anyone who chooses to step outside the purely corporeal walks--wether mystic saints (like St. Andrew or Hildegaard of Bingen), or diabolists--because through one road in Broceliande one can come to Sarras, the Grail Castle...but all other roads lead in the end to "antipodean P'o-L'u" where the "headless Emperor walks ever backward." But, Williams maintains that it is from Broceliande that all artists draw their inspiration, that all poets inherit their craft (and, given Broceliande as Otherworld, SRL would seem to agree on this matter).

All of this is interesting because of the connections of William's Arthur poems to Lewis' Space Trilogy, and the figure of Merlin. In William's poetry, Merlin and his sister Brisien, are not what I'd call human--they are both originally from Broceliande. Merlin has power over Time, Brisien over Space, and their purpose is to shape Logres into something never seen before in the world: they are to blend the structured and ordered heirarchy of Byzantium (which represents the order and gradation of Heaven) with the fecund creativity of Broceliande, so that the Grail can be brought from the Land of the Trinity and reside in the material world. Of course, this fails, but it is interesting because of the hints that it is not over--that they may try again.

Now, I've stated elsewhere on the board that I believe Lewis was playing with this idea in That Hideous Strength--but his Merlin is definitely human. Of course, it is possible that Williams' Merlin was also, just that he and Brisien had travelled as mystics into Broceliande...I'm not sure.

But this raises the interesting question on whether or nor the act of creating art is in some sense magical; Tolkien believed it to be so (in fact, he proposed that it was "sub-creation" under the Will of God...something that Lewis definitely bought in to). It is clear that Williams believed this too, although he formulated it as Broceliande being the source of all inspiration. SRL makes the same point in the Song of Albion, where the danger of destroying the Otherworld is that nothing of the nobler sense of spirit will be available to those in the manifest world any longer.

|

|

|

|

Post by dinadan on Feb 18, 2005 11:20:38 GMT -5

I personally prefer that it stay in faerie--it is a potent natural force there, but is utterly un-natural here. Does that make sense? I was thinking this over last night during my 3 hour philosophy class (yes, I should have been paying attention, but oh well), and I decided to take this on. It's not so much that "Faerie" or Broceliande is un-natural. It's more that it is supra-natural. Or, to diagram it logically (and what an assumption to think that logic might apply there at all!) let's call Faerie A and the "real world" B, so that "All things B are part of A, but not all things A are part of B." The supra-natural realm of Broceliance is vital for us; it's the repository of all things imaginative, and thus the source of inspiration. However, there are rules governing the interractions between these things; it's not allowed for humans to directly use the power of Broceliande here (i.e. through magick), but it is allowed indirectly; sub-creation of artistic imagination takes place here, and the resullt is transposed there. However, the supra-natural contains things that we conceive of as angels and demons, but also things that I don't think we have any words for, that can operate in both realms. It's by no means a sharp division, and we can't know too much about it without breaking the "rule" of directly going there. Is that in any way sensible to you?...I've tried to put it back together from a rough point-sketch from my notebook last night...I'll be glad to try to elaborate further if its not clear. |

|

|

|

Post by Riothamus on Feb 18, 2005 12:08:57 GMT -5

Well, I was thinking more metaphorically, but yeah, that makes sense. (Incidentally, I think there's a distinct whiff of "sub-creation of artistic imagination takes place here, and the resullt is transposed there." in Tolkien's own "Leaf by Niggle")

Hmm.... I'll have to pick up "Concerning Fairy-Stories" and read it again. It's certainly an interesting idea.

|

|

|

|

Post by dinadan on Feb 18, 2005 12:10:18 GMT -5

Well, I was thinking more metaphorically, but yeah, that makes sense. (Incidentally, I think there's a distinct whiff of "sub-creation of artistic imagination takes place here, and the resullt is transposed there." in Tolkien's own "Leaf by Niggle") . In Smith of Wooton Major as well. |

|

|

|

Post by twyrch on Feb 18, 2005 15:52:34 GMT -5

In Smith of Wooton Major as well. I loved that Story.... Gave me the idea for my own story actually... |

|

|

|

Post by dinadan on Feb 18, 2005 16:15:21 GMT -5

Smith is a good story...and is exactly about this sort of thing we're talking about. Of course, Smith gets to go to Faerie, but it's a special dispensation thing--and he's not allowed to go there forever; kind of like the Pevensie kids and Narnia. It's allowed for some to go there, occasionally, when it will benefit them in some way. But, it's not a place that's beneficial, or even safe, for everyone (remember, with the mark of the Star on his forehead, Smith wouldn't have been safe from all the things there either).

|

|

|

|

Post by twyrch on Feb 18, 2005 16:20:10 GMT -5

Smith is a good story...and is exactly about this sort of thing we're talking about. Of course, Smith gets to go to Faerie, but it's a special dispensation thing--and he's not allowed to go there forever; kind of like the Pevensie kids and Narnia. It's allowed for some to go there, occasionally, when it will benefit them in some way. But, it's not a place that's beneficial, or even safe, for everyone (remember, with the mark of the Star on his forehead, Smith wouldn't have been safe from all the things there either). Unlike the Landover Series by Terry Brooks. Now here is a series full of magic and Faerie mists and many other "otherworldly" things... The main character, Ben Holiday, goes to the land and must stay to keep the land safe. He dedicates his life to Landover... |

|

|

|

Post by Riothamus on Feb 19, 2005 9:55:42 GMT -5

In Smith of Wooton Major as well. I had forgotton about that one. |

|

|

|

Post by twyrch on Feb 20, 2005 9:58:01 GMT -5

I had forgotton about that one. I love the way that story ended! I couldn't have been happier.  |

|

|

|

Post by ducklauncher on Feb 22, 2005 14:24:23 GMT -5

Going back to what was said earlier about the creative nature of art...It's immensely interesting to me the way different people view the process of art. A lot of people treat it as a discovery rather than a creation, but I've always found that to be problematic. Sometimes it seems like discovery; often when I'm writing, I'll come up with an idea and find I don't have to change anything to incorporate it because it's already there. But I think that's just a depth of the creation itself. It's almost as if you create something in its entirety, and you only become aware of its depth as you explore it.

Magic, I think, generally operates the same way. There's a sense to the way magic is used in a world, and that's why readers are so sensitive to anything that doesn't quite fit--like Tom Bombadil. The thing about Middle Earth is that it is so hugely detailed that even something incongrous like Bombadil becomes another layer of that creation.

|

|

|

|

Post by Riothamus on Feb 24, 2005 8:29:04 GMT -5

Good point. But to what extent is the artist creating, and to what extent is he bringing the unconcious to light? It could be that, just as in Adam there were the potentialities of the entire human race, so too in the artist there are the potentialities of a thousand works of art.

Just throwing somthing out there.

|

|